Die Klimakrise stoppen – wie sollte das noch gehen? Ehrlich! In dieser Hinsicht bin ich ja Klimaskeptiker, als dass ich der Überzeugung bin, dass wir den Tanker schon zu lange und mit zu hoher Geschwindigkeit fahren, als dass wir seinen Kurs noch gravierend verändern könnten. Graeme Sait in seiner Präsentation nennt dazu auch eine Zahl: Selbst wenn wir morgen alle CO2-Emissionen einstellen würden, dann wäre in 200 Jahren die Konzentration von CO2 in der Atmosphäre immer noch so hoch wie 1975. Und damit weiterhin viel zu hoch. Und das wäre, wenn wir morgen… Vielleicht sind wir in 50 Jahren bei -80%. Vielleicht…

Auch interessant: 476 Milliarden Tonnen CO2, die ursprünglich im Boden (also diesem meist krümeligen Gemisch aus Ton, Schluff und Lehm plus organischen Anteilen) waren, sind durch die Landwirtschaft in der Atmosphäre gewandert. Im Vergleich dazu machen sich die 250 Milliarden Tonnen, die durch die Verbrennung von Kohle und Erdöl in die Luft gepustet wurden, doch noch relativ klein aus.

50% aller der Menschen gemachten CO2 Emissionen haben die Ozeane absorbiert. Mit zukünftig verheerenden Folgen: Graeme Sait benennt diese Problematik als ernster und dringlicher als die Klimaveränderung! Denn durch das CO2 wird der Ozean saurer. Und das hat Auswirkungen auf z.B. die Korallen (was viele mittlerweile wissen), aber auch auf das Phytoplankton, welches wiederum 50% des Sauerstoff produzieren, den wir einatmen.

Ach so, bevor ich es vergesse: Es gäbe da vielleicht eine Lösung. Und das wäre der Aufbau von Humus. Mit einer veränderten Bearbeitung unserer Böden – wenn dies eine globale Aktion wäre – könnten wir es vielleicht schaffen, grosse Teile des CO2’s aus der Atmosphäre zu ziehen und diese im Boden zu binden. Darin sind sich viele Wissenschaftler einig (mehr dazu in den nächsten Wochen hier). Worauf warten noch?!

co2

Flug nach San Francisco – fünf Quadratmeter Arktiseis weg

Ein Flug von Frankfurt nach San Francisco und zurück lässt fünf Quadratmeter Arktiseis verschwinden. Pro Passagier. Ein deutsch-amerikanisches Forscherduo macht jetzt diese genauso simple wie verstörende Rechnung auf. Hier zum Artikel auf Spiegel-Online. Hier zur wissenschaftlichen Publikation.

Buch: Terra Preta. Die schwarze Revolution aus dem Regenwald. Ute Scheub

Eine lesenswerte Übersicht zum (breit aufgefächerten) Thema Terra Preta hat Ute Scheub in ihrem Buch „Terra Preta. Die schwarze Revolution aus dem Regenwald“ zusammengefasst. Ausgehend von der derzeitigen Problematik der industriellen Landwirtschaft (v.a. in Hinsicht auf den Bodenverlust), stellt Frau Scheub die Entdeckung und Entwicklung der Schwarzen Erde, wie sie im Amazonas entdeckt wurde, vor, und zeigt auf welches Potential die Verwendung von Pflanzenkohle (in Verbindung mit Kompost, EM, Urin usw.) hat. Sehr schön zu lesen, flüssig geschrieben, mit interessanten Fakten und Zahlen gespickt, ist dieses Buch sicher ein gutes Aufklärungswerk. Das Wie? der Herstellung von Pflanzenkohle kommt dann aber doch nur sehr kurz vor, ohne Anleitungen – Schade. Auch bin ich mir nicht ganz sicher ob der Hype gerechtfertigt ist, da es noch sehr wenige wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zu den Effekten gibt; und unklar bleibt mir auch noch wo das ganze Material herkommen soll, was wir dann zu Pflanzenkohle verarbeiten bzw. in wieweit da Konkurrenz zwischen Generierung von Pflanzenkohle, Kompost, Wärmegewinnung u.a. eine Rolle spielen. Vielleicht haben da andere noch harte Fakten zu… Ingesamt ein sicher empfehlenswertes Buch, was zum einen nachdenklich macht über unsere derzeitige Situation und unserem Umgehen mit Erde, Landwirtschaft, Nahrungsmitteln und Konsum – und zum anderen auch Hoffnung gibt, dass es sinnvolle Lösungen gibt, wenn wir sie denn nutzen.

Ithaka, Kon-tiki und Terra Preta

Für die Terra-Preta Fans, und solche die es werden wollen, hier ein Link zum Ithaka-Journal. Entstanden in einer Zusammenarbeit mit Delinat, einem Bio-Wein-Versandhandel (mit ziemlich hohem ökologischen Anspruch), forscht v.a. Hans-Peter Schmidt dort mit Pflanzenkohle im Weinberg, und seit einigen Jahren zunehmend in Nepal. Obwohl ich selbst dem Terra-Preta-Hype etwas reserviert gegenüber stehe, scheinen mir seine Untersuchungen, Anwendungen Entwicklungen sehr interessant und lesenswert zu sein. Einfach mal reinschauen.

Doku: Soil Carbon Cowboys

Die Welt retten – d.h. u.a. die Klimaveränderung stoppen – und gleichzeitig bessere Ernten einfahren. Unter diesem Motto bewegt sich ziemlich viel im englisch-sprachigen Raum, unter dem Begriff des Carbon Farming. Auch Regenrative Agriculture hat einen ziemlich Schwerpunkt darauf – vielleicht weil sich das momentan so gut verkaufen lässt. In jedem Fall: Was so manche Menschen (z.B. Allan Savory) seit Jahrzehnten predigen, das scheint sich so langsam durchzusetzen. Naja, durchsetzen ist da sicher doch nicht das richtige Wort. In dieser kurzen Doku jedenfalls berichten ein paar Farmer in den USA über ihre Erfahrungen im Dreieck Mensch, Tier und Boden. Und diese Erfahrungen sind richtig, richtig, richtig gut!

Lesenswerte Artikel

Treibhausgase: Forscher ermitteln Chinas Beitrag zur Klimaerwärmung. Fast ein Viertel des Treibhausgases CO2 stammt mittlerweile aus China – dennoch ist das Land derzeit nur für ein Zehntel der Erwärmung verantwortlich, sagt eine Studie. Sie liefert noch weitere Überraschungen.

Erfolg im Klimaschutz: Energiebedingter CO2-Ausstoß steigt nicht weiter. Fortschritte bei der Eindämmung des CO2-Ausstoßes: Zwei Jahre nacheinander sind die globalen Emissionen durch die Energieerzeugung nicht gestiegen. In Deutschland schwärzen Stromexporte die CO2-Bilanz.

Treibhausgas: CO2 macht großen Sprung. Das Treibhausgas CO2 gilt als Treiber der Klimaerwärmung. Nun melden Forscher die schnellste Zunahme des Gases seit Beginn der Messungen.

Lesenswerte Artikel

Erneuerbare Energien: Windräder nehmen sich gegenseitig den Wind aus den Rotorblättern. Sie liefern den größten Anteil erneuerbarer Energie: Windparks. Doch die Technologie stößt schneller an ihre Grenzen als bislang gehofft – stehen Windräder nah beieinander, bremsen sie sich gegenseitig aus.

Klimaschutz-Zertifikate: Die Gelddruckmaschine. Der Zertifikate-Handel war mal eine gute Idee: Das Klima sollte davon profitieren. Doch tatsächlich bereicherten sich oft nur Geschäftemacher. Eine Studie zeigt, wie dreist bei internationalen Klimaschutzprojekten getrickst wurde.

Ozeane: Weltweit verlieren Korallen ihre Farben. Erhöhte Wassertemperaturen setzen den Korallen weltweit zu: Aus farbenprächtigen Riffen wird eine blasse Ödnis. Die Fische bleiben fern, und auch der Mensch könnte die Folgen des Korallensterbens zu spüren bekommen.

Zum Klima-Gipfel. Interessante Artikel

Hat eigentlich jemand mal errechnet wie viel CO2 in die Luft gepustet wird, damit sich alle Regierungschef mit grossem Anhang, sowie die ganzen NGOs in Paris treffen können? Bei dieser Konferenz, wo wir vorher schon wissen, dass nicht viel bei heraus kommt? Ich persönlich habe da jegliche Hoffnung verloren, dass die Staatschefs zu guten Ergebnissen kommen werden – auch weil letzten Endes die Menschen dahinter (also: wir) unseren Lebensstil kaum ändern wollen. Das verlängerte Wochenende mal nach Barcelona, die lange Wintersaison auf Malta unterbrechen, ein neues (Benzin-sparendes oder sogar noch besser: Elektro-) Auto, ein neues Handy jedes Jahr, usw….. Wie soll da CO2 eingespart werden?

Jedenfalls, passend zum Gipfel, ein paar Verweise auf interessante Artikel.

Klimagipfel in Paris: Der Sinn des Irrsinns: Der Klimagipfel von Paris wird die Welt nicht retten. Es wird hier keinen Vertrag geben, der das Problem der Erderwärmung löst. Und trotzdem braucht es dieses Treffen.

Klimawandel: Wie ich einen Tag lang CO2 sparte: Zwei Wochen lang verhandeln Diplomaten auf dem Uno-Gipfel in Paris um die Klimazukunft der Erde. Die Autorin Carolin Wahnbaeck hat einen Tag lang mit sich selbst gerungen, um ihre CO 2 -Bilanz zu verbessern. Am Ende wurde es grundsätzlich.

„Ein Flug – und fast alle anderen CO2-Einsparungen im Alltag verblassen dagegen“, sagt Michael Bilharz, Experte für den CO2-Rechner vom Umweltbundesamt. Zwar seien kleine Maßnahmen wie die ausgeschaltete Kaffeemaschine oder das einmal stehen gelassene Auto sicher sinnvoll. „Was aber wirklich zählt, sind die Grundsatzentscheidungen rund um die Themen Verkehr, Heizung, Fleischkonsum und Haushaltsgroßgeräte“, sagt Bilharz.

Kapitalismus-Kritik: „Nur arme Staaten sollten wachsen“:

Flüchtlinge, Klimawandel, Bankenbeben – die großen Krisen hängen eng zusammen, sagt der Nachhaltigkeitsforscher Reinhard Loske. Er prophezeit das Ende der weltweiten Wachstumspolitik und fordert eine radikale Reform des Kapitalismus.

Lesenswerte Artikel

Meeresforschung: Plastikmüll hat die Arktis erreicht. Eigentlich wollten die Polarforscher Meeressäuger und Seevögel beobachten – doch dann zählten sie auch Müll. Selbst im hohen Norden treibt Kunststoffschrott im Wasser und wird zur Gefahr für die dort lebenden Arten.

Umweltkatastrophe in Indonesien: Ein Land ringt nach Luft. Brandrodung und Dürre haben in Indonesien eine Klimakatastrophe ausgelöst, die globale Auswirkungen haben könnte. Millionen Menschen leiden unter beißendem Smog, auch seltene Wildtiere wie der Orang-Utan sind bedroht.

Klima: China stößt weitaus mehr Kohlendioxid aus als bekannt. Chinas riesiger Treibhausgas-Ausstoß bestimmt wesentlich, wie stark sich das Klima erwärmen wird. Jetzt wird bekannt: Die CO2-Emissionen liegen um ein Sechstel höher als angegeben.

Da haben wir es: Die globale Erwärmung erreicht die Ein-Grad-Schwelle

Die Weltgemeinschaft möchte die globale Erwärmung auf zwei Grad begrenzen. Neue Daten zeigen: Die Hälfte ist erreicht. 2015 dürfte die Ein-Grad-Marke knacken. Das ist zwar teils „nur“ möglich gewesen dank El Nino. Jedoch: Es gab ja nun schon früher viele El Ninos, und die 1°-Marke wurde nie überschritten. Tja, wir sind auf dem besten Wege zu Klimaveränderungen, die dramatische Auswirkungen haben werden. Das 2°C-Ziel ist, meiner Meinung nach, so gut wir komplett unrealistisch. Wer fängt denn nun wirklich an, weniger CO2 in die Luft zu blasen? Gerade erst wurde ja vorgerechnet, dass China sogar noch höhere Emissionen hat als die Zahlen die angegeben wurden. Und von einer Reduzierung sind wir in fast allen Ländern der Erde weit entfernt.

Hier der Artikel im Spiegel, hier in der englischen Quelle.

Fleischkonsum und CO2-Emissionen. Was hat das eine mit dem anderen zu tun?

Die Landwirtschaft hat ja bekanntermassen einen grossen Anteil an den vom Menschen verursachten Treibhausgasemissionen. Einen ziemlich grossen Anteil daran hat die Tierhaltung – wobei hier unterschieden werden muss zwischen „natürlicher“ und industrieller Tierhaltung. Zum einen weil Regenwälder abgeholzt werden um dann großflächig (meist Gen-manipuliertes) Soja (mit hohem Herbizideinsatz – Monsanto lässt grüssen) anzubauen; zum anderen weil dann dieses Soja nach Europa geschifft wird um dort in den Massentierhaltungen die Tiere damit zu füttern, die wiederum solche Mengen von Gülle produzieren, dass diese nicht mehr „natürlich“ verarbeitet und ausgebracht werden kann. Wie Joel Salatin sagt: Da wo es stinkt, stimmt was nicht. Zu diesem Thema habe ich vor ein paar Jahren mal einen Artikel geschrieben, den ich hier mal mit euch teilen will. An sich hat sich an der Situation nichts verändert, im Gegenteil. Ausser der Erkenntnis, dass der Ansatz des Holistic Managements von Allan Savory mich davon überzeugt hat dass „richtiges“, der Natur abgeschautes und an die Natur angepasstes Weidemanagement ein riesiges Potential zur Bodenverbesserung, „Renaturierung“ und CO2-Speicherung bietet.

Präsentation: Saul Griffith on Energy Use

Schon ein paar Jahre alt, aber immer wieder sehenswert. Saul Griffith, Erfinder und Ingenieur erklärt wie unser Leben in die Energieeinheit Watt umgerechnet werden kann, wie viel es davon braucht um dieses zu „powern“ und v.a. was es bräuchte um diese Energie nachhaltig zu gewinnen. Ziemlich beeindruckend und zur gleichen Zeit auch echt deprimierend, wenn man hört wie viele Wind- und Solaranlagen neu gebaut werden müssten um innerhalb von kürzerer Zeit den CO2-Ausstoss und die Abhängigkeit von Kohle und Öl deutlich zu reduzieren.

Buch: Humusaufbau. Chance für Landwirtschaft und Klima. Gerald Dunst

Mir kommt es schon immer öfter so vor, als wenn wir in einer Zeit der Bewusstseinsveränderung leben. Ohne dabei arg ins Spirituelle gehen zu wollen, so fallen mir die grosse Anzahl an Gesellschafts-kritischen Dokumentationen und Büchern sehr auf. Auch beim sträflichst vernachlässigtem Thema Boden schiessen die Bücher nur so aus diesem. „Humusaufbau. Chance für Landwirtschaft und Klima“ von Gerald Dunst ist ein solches. Es ist weniger „wissenschaftlich“ oder „historisch“ wie andere Werke; dafür aber geschrieben von einem Praktiker, und zwar dem Praktiker schlechthin. Mitbegründer der Bewegung „Ökoregion Kaindorf“, von der hier auch schon die Rede war, Betreiber einer grossen Kompostfirma mit vielen langjährigen Versuchen auf landwirtschaftlichen Flächen. Gut geschrieben, anschaulich, verständlich, sachlich. Absolut empfehlenswert!

Mir kommt es schon immer öfter so vor, als wenn wir in einer Zeit der Bewusstseinsveränderung leben. Ohne dabei arg ins Spirituelle gehen zu wollen, so fallen mir die grosse Anzahl an Gesellschafts-kritischen Dokumentationen und Büchern sehr auf. Auch beim sträflichst vernachlässigtem Thema Boden schiessen die Bücher nur so aus diesem. „Humusaufbau. Chance für Landwirtschaft und Klima“ von Gerald Dunst ist ein solches. Es ist weniger „wissenschaftlich“ oder „historisch“ wie andere Werke; dafür aber geschrieben von einem Praktiker, und zwar dem Praktiker schlechthin. Mitbegründer der Bewegung „Ökoregion Kaindorf“, von der hier auch schon die Rede war, Betreiber einer grossen Kompostfirma mit vielen langjährigen Versuchen auf landwirtschaftlichen Flächen. Gut geschrieben, anschaulich, verständlich, sachlich. Absolut empfehlenswert!

Artikel: Kohl fürs Klima

Ein einzigartiger CO2-Deal: Bauern in Österreich binden Treibhausgase und werden dafür von Firmen bezahlt. Diese werben dann mit Klimaneutralität.

KAINDORF taz | Der Anfang war nicht einfach für Bauer Johann Gradwohl: Der Kompost, mit dem er seine Felder düngte, brachte auch das Unkraut mächtig zum Wachsen. Doch sein Lohn war ein fruchtbarer Boden. Gradwohl ist einer von sieben Landwirten in der österreichischen „Ökoregion Kaindorf“, die Chinakohl als „Klimakohl“ anbauen; in der letzten Saison waren es etwa 700 Tonnen.

Neben Kohl produzieren sie auch Erdbeeren, Karotten und Cocktailtomaten, die die „Spar“-Handelskette in ihren 1.500 Filialen in ganz Österreich als „Humusgemüse“ verkauft. „Die Kunden reißen uns die Produkte aus den Händen“, freut sich „Spar“-Chef Gerhard Drexler.

Die Idee mit „Klimakohl“ könnte man als „Abfallprodukt“ einer pfiffigen Nachhaltigkeitsinitiative bezeichen, wenn es den Engagierten in der Steiermark nicht gerade darum ginge, Abfälle zu vermeiden und im Kreislauf zu wirtschaften. Die mit mehreren Umweltpreisen ausgezeichnete „Ökoregion Kaindorf“, die die sechs ländlichen Gemeinden Dienersdorf, Ebersdorf, Hartl, Hofkirchen, Kaindorf und Tiefenbach umfasst, hat sich das ehrgeizige Ziel gesetzt, bis zum Jahr 2020 CO2-neutral zu werden – unter anderem durch erneuerbare Energien und Humusaufbau.

Auf Initiative des 2007 gegründeten Vereins Ökoregion Kaindorf ist ein weltweit einzigartiger regionaler Handel mit CO2-Zertifikaten initiiert worden: Gewerbeunternehmen, die CO2-neutral produzieren wollen, schließen mit Landwirten, die über den Humus Kohlenstoff im Boden binden, freiwillig einen Vertrag ab.

Preisgekrönter Kompostbetrieb

Wie funktioniert das? Böden sind der größte Treibhausgasspeicher auf Erden, sie speichern mehr CO2 in Form von Kohlenstoff als Ozeane und Wälder zusammen. Ein Bauer könne durch Humusaufbau das Äquivalent von 50 Tonnen CO2 pro Hektar und Jahr binden, erklärt Mitinitiator Gerald Dunst, dessen Kompostbetrieb „Sonnenerde“ mit dem österreichischen Klimaschutzpreis ausgezeichnet wurde. Dunst leitet die Arbeitsgruppe Landwirtschaft des Vereins Ökoregion Kaindorf und berät rund 200 bislang zumeist konventionell wirtschaftende Bauern beim Humusaufbau ihrer Äcker.

Auf Musterflächen haben sich die Humusgehalte durch die Einbringung von Kompost und Pflanzenkohle („Terra-Preta-Technik“), pfluglose Bodenbearbeitung, Winterbegrünung und Fruchtwechsel bereits auf sagenhafte sechs Prozent erhöht. Folge: Die Böden brauchen weder Dünger noch Pestizide, weil die Bodenfruchtbarkeit den Schädlingsbefall hemmt, und im Gegensatz zu früher können sie Starkregen vollständig aufsaugen und speichern.

Der Verein Ökoregion Kaindorf bezahlt Landwirten ein Erfolgshonorar von 30 Euro pro Tonne nachweislich gebundenes CO2, um deren Mehrkosten auszugleichen, erklärt der Landwirtschaftsberater das Prinzip dieses Zertifikathandels. Im Gegenzug verpflichten sich die Gärtnerinnen und Bauern, den Humusgehalt ihrer Böden über fünf Jahre stabil zu halten – was unabhängige Sachverständige mittels Bodenproben überprüfen.

Das Geld für die Zertifikate kommt von regionalen Unternehmen, die ihren unvermeidbaren CO2-Ausstoß kompensieren wollen. Beteiligt sind unter anderem eine Brauerei, ein Ökokaffeehandel, ein Malerbetrieb und eine Fleischerei. Sie bezahlen 45 Euro pro Tonne, wobei die Preisdifferenz an den Verein für dessen Aufbauarbeit geht. Ihr Gewinn: Sie können mit CO2-neutral hergestellten Produkten werben und auf diese Weise neue Kundschaft generieren. Eine Win-win-Situation für alle Beteiligten.

Die Fruchthandelskette Frutura wiederum hat eine langfristige Kooperation mit der Ökoregion und ihren Feldfruchtproduzenten vereinbart. Bis 2020 soll sämtliches Obst und Gemüse, das sie der „Spar“-Kette liefert, CO2-neutral produziert werden.

Manfred Hohensinner, früher selbst Landwirt, jetzt Geschäftsführer von Frutura, stimmt dieses neue Geschäftsmodell geradezu euphorisch: „Eine Riesenchance für die Bauernschaft“, jubelt er. „Die Bauern werden Klimaschützer!“ Auch aus deutschen Umweltbehörden sind Stimmen zu hören, dies sei der einzige funktionierende und sinnvolle CO2-Handel, weil nachweisbar und transparent auf die Region bezogen; auch das Geld bleibe in der Region.

Artikel: The Fight Against Global Warming: A Failure and A Fix

Sehr interessanter Artikel: Wie lange wird schon vor der menschengemachten Klimaerwärmung gewarnt? Wie viele Wissenschaftler sind sich seit Jahren einig? Wie oft ist demonstriert und lamentiert worden? Wie viele internationale Konferenzen gab’s? Und, was ist passiert? Rhetorische Fragen, die nur eins zeigen: Die Welt bewegt sich (in dieser Frage) nicht. Und Hoffnung ist nicht in Sicht. Zeit also die Strategie der Umweltschützer zu überdenken. Statt zu versuchen den CO2-Ausstoß zu senken, gäb’s da die Möglichkeit CO2 aus der Luft schnell, billig und effektiv zu binden. Und zwar mit den Ergebnissen die das Holistic Management v.a. in Afrika und den USA liefert. Wie schon in einigen Artikel hier zuvor aufgezeigt, besteht bei dieser Methode die Möglichkeit mittels gut überlegter Weidewirtschaft und der Einbeziehung verschiedener Umweltfaktoren, (fast) schon verloren gegangene Wiesen und Steppen, welcher mittlerweile die Verwüstung drohen, wieder in prächtige Landschaften zu verwandeln. Denn diese Grasvegetation benötigt, wie in einer Symbiose, dicht trampelnde und grasende Tiere um sich gut zu entwickeln. Und da ein großer Teil des Pflanzenwachstums im Boden, bei den Wurzeln stattfindet, können große Mengen CO2 langfristig gebunden werden. Wie gesagt: Sehr interessanter Artikel: The fight against global warming – a failure and a fix. (Hier lokal.)

Präsentation: Soil Carbon Putting Carbon Back Where It Belongs In The Earth. Tony Lovell

Interessanter Vortrag darüber was wir in Sachen „Bodenbehandlung“ oder eher „Bodennutzung“ (v.a. durch Nutztiere) falsch machen. Und wie es besser gehen könnten. Dabei bläst Tony Lovell ins gleiche Horn wie Seth Itzkan und Allan Savory: Eine kurzzeitige, intensive Bewirtschaftungsweise ist deutlich besser als eine extensive Weidehaltung. Dies zeigt er deutlich mit diesen Vergleichsbildern: Drei Orte, am gleichen Fluss, im gleichen Gebiet, unter gleichen Bedingungen. Der einzige Unterschied ist die Bewirtschaftungsintensität. Diese ist in der linken Reihe extensiv, in der rechten, angelehnt an das Vorbild Natur (siehe Bild oben, die grossen Herden Afrikas oder Nordamerikas, die kurz, dicht gedrängt, durch die Prärie ziehen):

Dieses Bild zeigt Gras, welches, im linken Bildbereich alle paar Tage gemäht worden ist, und im rechten seine natürliche Wuchsform entwickeln konnte. Interessant ist zu beobachten, dass der Teil der im Boden sich entwickelt – also die CO2-Speicherung in Form von Biomasse – deutlich höher ist. Und im Gegensatz zu Bäumen, wo das Verhältnis „über der Erde/unter der Erde“ mehr oder weniger 1:1 ist, ist dieser bei den Gräsern aber 1:4:

Growing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Due to Meat Production (Englisch)

Both intensive (industrial) and non-intensive (traditional) forms of meat production result in the release of significant amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs). As meat supply and consumption increase around the world, more sustainable food systems must be encouraged.

Why is this issue important?

For many thousands of years, mankind has lived in close proximity with numerous animal species, providing them with food and shelter in exchange for their domestic use and for products such as meat and milk, feathers, wool and leather. As the economy in some (mostly western) countries slowly grew, industrial style agriculture replaced traditional small-scale farming. Pasturage and use of animal manure as fertilizer was abandoned. The increasing efficiency of industrial agriculture has led to reduced prices for many of our daily products. It helped to reliably nourish large populations, and turned a food that was an occasional meal—meat—into an affordable, every-day product for many (Figure 1).

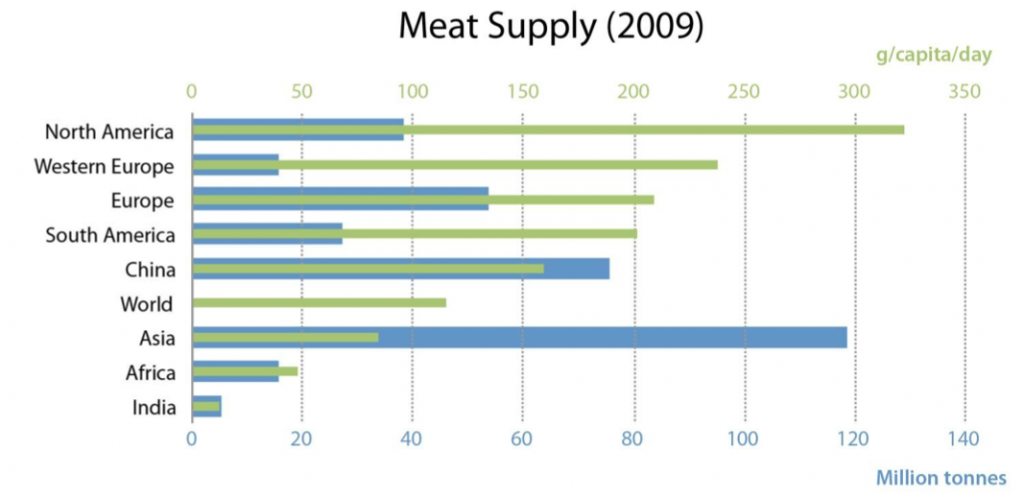

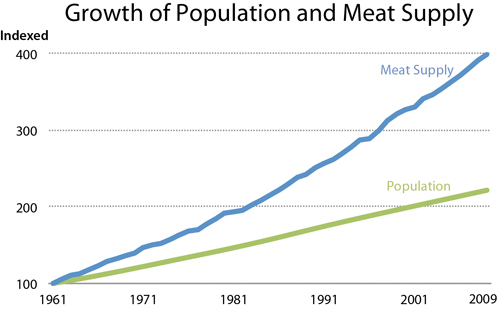

Figure 1: Growth of population and meat supply, indexed 1961=100 (FAO 2012a, UN 2012)

However, the true costs of industrial agriculture, and specifically „cheap meat“, have become more and more evident. Today, „the livestock sector emerges as one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems“ (Steinfeld et al. 2006). This includes stresses such as deforestation, desertification, „excretion of polluting nutrients, overuse of freshwater, inefficient use of energy, diverting food for use as feed and emission of GHGs“ (Janzen 2011). Perhaps the most worrisome impact of industrial meat production, analyzed and discussed in many scientific publications in recent years, is the role of livestock in climate change. The raising of livestock results in the emission of methane (CH4) from enteric fermentation1 and nitrous oxide (N2O) from excreted nitrogen, as well as from chemical nitrogenous (N) fertilizers used to produce the feed for the many animals often packed into „landless“ Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) (Lesschen et al. 2011, Herrero et al 2011, O’Mara 2011, Janzen 2011, Reay et al. 2012).

What are the findings?

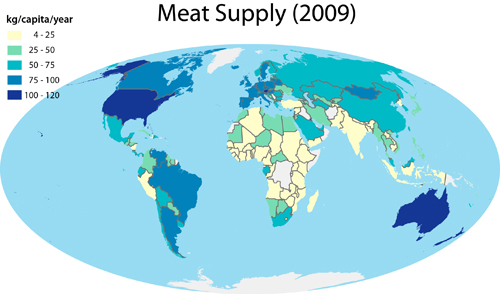

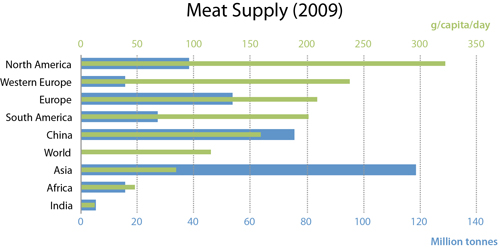

Meat Supply

Meat supply varies enormously from region to region, and large differences are visible within regions (Figures 2-4). The USA leads by far with over 322 grams of meat2 per person per day (120 kg per year), with Australia and New Zealand close behind. Europeans consume slightly more than 200 grams of meat (76 kg per year); almost as much as do South Americans (especially in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela). Although Asia’s meat consumption is only 25 per cent of the U.S. average (84 grams per day, 31 kg per year), there are large differences, for example, between the two most populous countries: China consumes 160 grams per day, India only 12 grams per day. The average meat consumption globally is 115 grams per day (42 kg per year).

Figure 2: Meat supply around the world (kg/capita/year) (FAO 2012a)

Figure 3: Meat supply (g/capita/day and tonnes) for selected countries/regions (FAO 2012a)

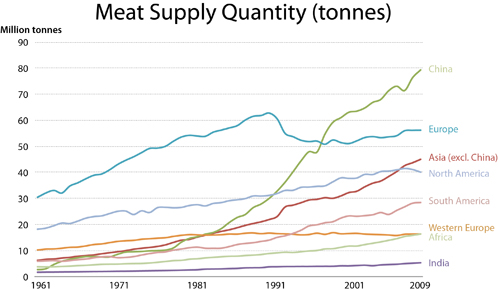

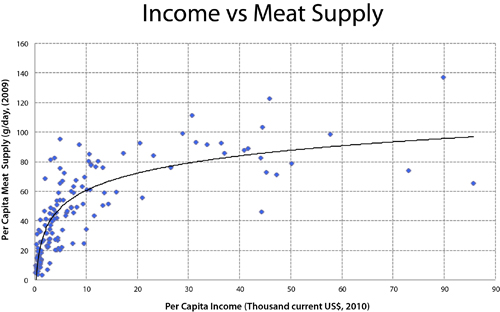

Over the past few decades, meat supply has grown in most of the world’s regions (Figure 4), with Europe being the main exception. The growth in per capita consumption is strongly linked to increasing levels of income in many countries of the world (Figure 5). Higher incomes translate into demand for more valued, higher protein nutrition (Delgado et al. 1999). The effect of increased income on diets is greatest among lower- and middle-income populations (WRI 2005). One of the fastest growing meat consuming regions is Asia, particularly China. Total meat consumption has increased 30-fold since 1961 in Asia, and by 165 per cent since 1990 in China. Per capita meat consumption has grown by a factor of 15 since 1961 in Asia and by 130 per cent since 1990 in China (FAO 2012a).

Figure 4: Trends in meat supply for selected countries/regions between 1961 and 2009 (FAO 2012a)

Figure 5: Per capita income versus meat consumption (FAO 2012a, World Bank 2012)

Not only has per capita consumption grown, but there are also millions more consumers of meat. The global human population grew from around 5 billion in 1987 to 7 billion in 2011, and is expected to reach 9 billion people in 2050. Thus, the total amount of meat produced climbed from 70 million tonnes in 1961 to 160 million tonnes in 1987 to 278 million tonnes in 2009 (FAO 2012a), an increase of 300 per cent in 50 years (Figure 1). The FAO (Steinfeld et al. 2006) expects that global meat consumption will rise to 460 million tonnes in 2050, a further increase of 65 per cent within the next 40 years.

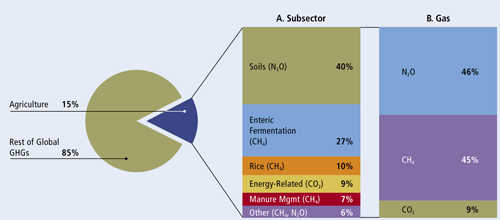

The role of (animal) agriculture in climate change

Agriculture, through meat production, is one of the main contributors to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and thus has a potential impact on climate change. Estimates of the total emissions from agriculture differ according to the system boundaries used for calculations. Most studies attribute 10-35 per cent of all global GHG emissions to agriculture (Denman et al. 2007, EPA 2006, McMichael 2007, Stern 2006). Large differences are mainly based on the exclusion or inclusion of emissions due to deforestation and land use change.

Recent estimates concerning animal agriculture’s share of total global GHG emissions range mainly between 10-25 per cent (Steinfeld et al. 2006, Fiala 2008, UNEP 2009, Gill et al. 2010, Barclay 2012), where again the higher figure includes the effects of deforestation and other land use changes and the lower one does not. According to Steinfeld et al. (2006) and McMichael et al. (2007), emissions from livestock constitute nearly 80 per cent of all agricultural emissions.

Types of emissions

In contrast to general trends of GHG emissions, carbon dioxide (CO2) is only a small component of emissions in animal agriculture. The largest share of GHG emissions is from two other gases: methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). These are not only emitted in large quantities, but are also potent greenhouse gases, with a global warming potential (GWP3) of 25 using a 100-year timeframe for methane and a GWP of 296 for N2O.

Globally, about 9 per cent of emissions in the entire agricultural sector consist of CO2, 35-45 per cent of methane and 45-55 per cent of nitrous

oxide (WRI 2005, McMichael et al. 2007, IPCC 2007) (Figure 6).

Figure 6: GHG emissions from agriculture (WRI 2005)

The main sources of CH4 are the enteric fermentation of ruminants and releases from stored manure, which also emits N2O. The application of manure as well as N fertilizers to agricultural land increases emissions of N2O. Furthermore, N2O as well as CO2 are released during production of chemical N fertilizers. Some CO2 is also produced on farms from fossil fuels and energy usage and, as some authors highlight, by the exhalation of animals, which is generally not taken into account (Goodland and Anhang 2009, Herrero et al. 2011). Additionally, deforestation and conversion of grassland into agricultural land release considerable quantities of CO2 and N2O into the atmosphere, as the soil decomposes carbon-rich humus (FAO 2010). In Europe (the EU-27), for example, enteric fermentation was the main source (36 per cent) of GHG emissions in the livestock sector, followed by N2O soil emissions (28 per cent) (Lesschen et al. 2011). Livestock are also responsible for almost two-thirds (64 per cent) of anthropogenic ammonia emissions, which contribute significantly to acid rain and acidification of ecosystems (Steinfeld et al. 2006).

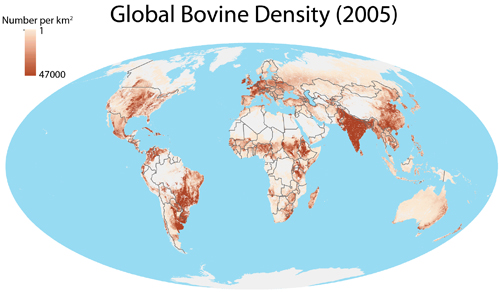

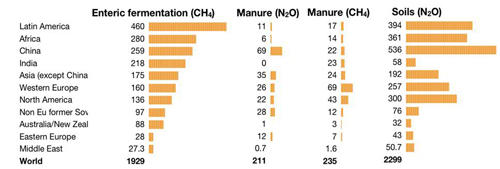

Amount and geographic distribution of bovine animals and emissions

Cattle are by far the largest contributors to global enteric CH4 emissions, as they are the most numerous and have a much larger body size relative to other species such as sheep and goats. Out of the 1.43 billion cattle (FAO 2012a) (Figure 7) in 2010, 33 per cent were in Asia, 25 per cent in South America and 20 per cent in Africa. Asia is the main source of CH4 emissions, with almost 34 per cent of global emissions (Figure 8). China is a major source of enteric emissions and, while Indians are low meat consumers, India as a country also has high levels of CH4 emissions. Latin America follows with 24 per cent and Africa with 14.5 per cent. China, Western Europe and North America are the regions with the highest emissions from manure.

Figure 7: Bovine density distribution worldwide (FAO 2012b)

Figure 8: Regional emissions of major agricultural greenhouse gases (million tonnes of CO2-eq/year)

(EPA (2006) and O’Mara (2011), re-expressed by the author)

Emissions for a meal

In an analysis of the EU-27 countries, „beef had by far the highest GHG emissions with 22.6 kg CO2-eq/kg“4(Lesschen et al. 2011) in comparison to other products such as pork (2.5), poultry (1.6) and milk (1.3). A study in the UK found that emissions from beef amount to 16 kg CO2-eq/kg beef compared to 0.8 kg CO2-eq/kg of wheat (Garnett 2009). In an analysis of commonly consumed foods in Sweden, the total GHG emissions for beef summed up to 30 kg CO2-eq/kg beef (Carlsson-Kanyama and González 2009).The authors conclude that „it is more “climate efficient“ to produce protein from vegetable sources than from animal sources“, and add that „beef is the least efficient way to produce protein, less efficient than vegetables that are not recognized for their high protein content, such as green beans or carrots“. In terms of GHG emissions „the consumption of 1 kg domestic beef in a household represents automobile use of a distance of ~160 km (99 miles)“ (Carlsson-Kanyama and González 2009). By one estimate, about 35 kilojoules (kJ) of fossil energy are required to produce 1 kJ of beef raised in a CAFO/feedlot (Hillel and Rosenzweig 2008).

Animal Feed and Manure

Under natural conditions which were maintained for thousands of years and still widely exist around the world, there is a closed, circular system, in which some animals feed themselves from landscape types which would otherwise be of little use to humans (Garnett 2009, UNEP 2012). They thus convert energy stored in plants into food, while at the same time fertilizing the ground with their excrements. Although not an intensive form of production, this co-existence and use of marginal resources was, and still is in some regions, an efficient symbiosis between plant life, animal life and human needs. (Godfray et al. 2010, Janzen 2011)

In many parts of the world „traditional“ forms of animal agriculture have to a certain extent been replaced by a „landless“, high-density, industrial-styled animal production system, exemplified by the phenomenon known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO). Those „factories“ hold hundreds or thousands of animals, and often buy and import animal feed from farmers far away. The feeding of livestock, and their resulting manure, contributes to a variety of environmental problems, including GHG emissions (Janzen 2011, Lesschen et al. 2011). High-energy feed is based on soya and maize in particular, cultivated in vast monocultures and with heavy use of fertilizers and herbicides. It is then imported (at least in Europe and most parts of Asia) from countries as far away as Argentina and Brazil (Steinfeld et al. 2006). This has serious consequences in terms of land-use change in those feed-for-export production countries. Furthermore, this manure is generated in huge quantities. In the USA alone, operations which confine livestock and poultry animals generate about 500 million tonnes of manure annually, which is three times the amount of human sanitary waste produced annually (EPA 2009). Insufficient amounts of land on which to dispose of the manure results in the runoff and leaching of waste into and the contamination of surface and groundwater.

What are the implications and potential solutions?

Livestock in many regions of the world, and especially in dry areas, act as a „savings bank“ (Oenema and Tamminga 2005): a principal way of making use of a harsh environment, a „setting aside“ of food (and more generally, the value of this resource) for dry times, a main source of high-protein food. It contributes important non-food goods and services. Livestock rearing and consumption in these regions is a way of life, critical to pastoralists‘ identity, and should be protected and supported.

At present, the ecological foundations of agriculture are being undermined (UNEP 2012). At the same time, industrial agriculture is itself contributing to environmental problems such as climate change. However, there are mitigation techniques to reduce the impact of both intensive and non-intensive animal production on climate (McMichael et al. 2007, Gill et al. 2010, O’Mara 2011, Lesschen et al. 2011). Most of these are related to soil carbon sequestration5, „which was estimated to contribute 89 per cent of the technical mitigation potential“ (O’Mara 2011). Many of them have costs of implementation substantially reducing their potential. A reduction of non-carbon dioxide emissions of up to 20 per cent should, however, be possible at realistic costs (McMichael et al. 2007). Other mitigation solutions include improved feedstock efficiency and diets; the reduction of food waste and improved manure management (Steinfeld et al. 2006, McMichael et al. 2007). Farm scale and landscape scale strategies for making agriculture more sustainable are further outlined in Avoiding Future Famines (UNEP 2012).

Changes in human diet may also be a practical tool to reduce GHG emissions. As a large percentage of beef is consumed in hamburgers or sausages, „the inclusion of protein extenders from plant origin would be a practical way to replace red meats“ (Carlsson-Kanyama and González 2009). A switch to less „climate-harmful“ meat may also be possible, as pigs and poultry produce significantly less methane than cows. They are however more dependent on grain and soy-products and may thus still have a negative impact on GHG emissions (Barclay 2011). Grass-fed meat and resulting dairy products may be more environmentally friendly than factory-farmed or grain-fed options. Labeling of products, indicating the type of animal feed used, could allow consumers to make more informed choices (FOE 2010).

Scientists agree that in order to keep GHG emissions to 2000 levels the projected 9 billion inhabitants of the world (in 2050) need to each consume no more than 70-90 grams (McMichael et al. 2007, Barclay 2011) of meat per day. To meet this target, substantial reductions in meat consumption in developed countries and constrained growth in demand in developing ones would be required. A reduction in the consumption of meat, especially red meat, could have multiple health benefits, as there is clear evidence of a link between high meat diets and bowel cancer and heart disease (FOE 2010). A study modeling consumption patterns in the United Kingdom estimates that a 50 per cent reduction in meat and dairy consumption, if replaced by fruit, vegetable and cereals, could result in a 19 per cent reduction in GHG emissions and up to nearly 43,600 fewer deaths per year in the UK (Scarborough et al. 2012). However, the health effects of nutrient deficiencies that may result from reduced meat and dairy consumption still would need to be examined.

In short, the human health implications of a reduced meat diet need further exploration, but it seems probable that many benefits would accrue from lower consumption rates in many developed and some developing countries. At the same time, reduced meat production would ease both pressures on the remaining natural environment (i.e. less new land clearance for livestock) and on atmospheric emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O. As changing the eating habits of the world’s population will be difficult and slow to achieve, a long campaign must be envisioned, along with incentives to meat producers and consumers to change their production and dietary patterns. „Healthy“ eating is not just important for the individual but for the planet as a whole.

1 In the normal livestock digestive process microbes in the animal’s digestive system ferment food, converting plant material into nutrients that the animal can use. This fermentation process, known as enteric fermentation, produces methane as a by-product.

2 Roughly, the equivalent of three hamburgers.

3 GWP compares other gases‘ warming potency to that of CO2, which has its GWP set at 1.

4 The term „CO2 equivalent“ is a metric measure used to compare the emissions from various greenhouse gases on the basis of their global-warming potential (GWP), by converting amounts of other gases to the equivalent amount of carbon dioxide with the same global warming potential“ (Eurostat n.d.).

5 Soil carbon sequestration is the process of capturing atmospheric CO2 and storing it over long time in the soil.

Acknowledgement

Written by: Stefan Schwarzera, b with inputs from and editing by Ron Witta and Zinta Zommersc.

Production and Outreach Team: Arshia Chanderd, Erick Litswac, Kim Giesed, Michelle Anthonyd, Reza Hussaind, Theuri Mwangid.

(a UNEP/DEWA/GRID-Geneva, b University of Geneva, c UNEP/DEWA/Nairobi, d UNEP GRID Sioux Falls )

References

Barclay, J. M.G. (2012). Meat, a damaging extravagence: a response to Grumett and Gorringe. The Expository Times. 123(2) 70-73. doi: 10.1177/0014524611418580.

Carlsson-Kanyama, A., González, A. D. (2009). Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009; 89 (suppl): 1704S-9S. doi: 10.3945

Delgado, C., Rosegrant, M., Steinfeld, H., Ehui, S., Courbois, C. (1999). Livestock to 2020: The next food revolution. Food, Agriculture, and the Environment Discussion Paper 28. Washington, DC, IFPRI/FAO/ ILRI (International Food Policy Research Institute/ FAO/International Livestock Research Institute).

Denman, K.L., Brasseur, G., Chidthaisong, A., Ciais, P., Cox, P.M., Dickinson, R.E., Hauglustaine, D., Heinze, C., Holland, E., Jacob, D., Lohmann, U., Ramachandran, S., da Silva Dias, P.L., Wofsy, S.C., Zhang, X. (2007). Couplings between changes in the climate system and biogeochemistry. In: Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K.B., Tignor, M., Miller, H.L. (Eds.), Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 499–587.

Eurostat. (n.d.). Glossary:Carbon dioxide equivalent. Accessed online on Oct 22, 2012 at http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Glossary:CO2_equivalent

EPA (2006). Global Anthropogenic Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 1990-2020. United States Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 430-R-06-003, June 2006. Washington, DC, USA. www.epa.gov/nonCO2/econ-inv/dow.

EPA (2009). Compliance and Enforcement National Priority: Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). Accessed online on Oct 22, 2012 at http://www.epa.gov/oecaerth/resources/publications/data/planning/priorities/fy2008prioritycwacafo.pdf

FAO (2010). Greenhouse gas emissions from the dairy sector. A life cycle assessment. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

FAO (2012a). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Data accessed on Aug 30, 2012 at http://faostat.fao.org/

FAO (2012b). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Data accesses on Aug 30, 2012 at http://www.fao.org/geonetwork/srv/en/metadata.show?id=12713.

Fiala, N. (2008). Meeting the Demand: An Estimation of Potential Future Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Meat Production. Ecological Economics 67, 412-419.

FOE (2010). Healthy Planet Eating: How lower meat diets can save lives and the planet. Friends of the Earth.

Garnett, T. (2009). Livestock-related greenhouse gas emissions: impacts and options for policy makers. Environmental Science and Policy 12, 491–504.

Gill, M., Smith, P., Wilkinson, J.M. (2010). Mitigating climate change: the role of domestic livestock. Animal 4, 323–333.

Godfray, H.C.J., Beddington, J.R., Crute, I.R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J.F., Pretty, J., Robinson, S., Thomas, S.M., Toulmin, C. (2010). Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818.

Goodland, R., Anhang, J. (2009). Livestock and Climate Change. What if the key actors in climate change were pigs, chickens and cows? Worldwatch November/December 2009, Worldwatch Institute, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 10–19.

Herrero, M., Gerber, P., Vellinga, T. , Garnett, T. , Leip, A., Opio, C., Westhoek, H.J., Thornton, P.K., Olesen, J., Hutchings, N., Montgomery, H., Soussana, J.-F., Steinfeld, H., McAllister, T.A. (2011). Livestock and greenhouse gas emissions: The importance of getting the numbers right, Animal Feed Science and Technology, Volumes 166–167, 23 June 2011, Pages 779-782, ISSN 0377-8401, 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.04.083.

Hillel, D., Rosenzweig, C. (2008). Biodiversity and food production. In: Chivian, E., Bernstein, A. (Eds.), Sustaining Life – How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 325–381.

IPCC (2007). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Working group III. Climate change 2007: mitigation of climate change. Accessed online on Oct 22, 2012 at

http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_ipcc_fourth_assessment_report_wg3_report_mitigation_of_climate_change.htm

Janzen, H.H. (2011). What place for livestock on a re-greening earth? Animal Feed Science and Technology, 166-167, 783-796.

Lesschen, J.P., van der Berg, M., Westhoek, H.J., Witzke, H.P. and Oenema, O. (2011). Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 166-167, 16-28

McMichael, A.J., Powles, J.W., Butler, C.D. and Uauy, R. (2007). Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet 370, 1253–1263.

O’Mara, F.P. (2011). The significance of livestock as a contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions today and in the near future. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 166-167, 7-15.

Oenema, O. and Tamminga, S. (2005). Nitrogen in global animal production and management options for improving nitrogen use efficiency. Science in China Series C: Life Sciences 48, 871–887.

Reay, D.S., Davidson, E.A., Smith, K.A., Smith, P., Melillo, J.M., Dentener, F., Crutzen, P.J. (2012). Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nature Climate Change. Vol 2

Scarborough P, Allender S, Clarke D, Wickramasinghe K,and Rayner M. (2012) Modelling the health impact of environmentally sustainable dietary scenarios in the UK. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, doi:10.1038/ejcn.2012.34.

Steinfeld, H., Gerber, P., Wassenaar, T., Castel, V., Rosales, M. and de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy.

Stern, N. (2006). The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

UN (2012). UN Data. United Nations. Data accessed on Aug 30, 2012 at http://data.un.org/

UNEP (2009). The environmental food crisis – The environment’s role in averting future food crises. United Nations Environment Programme, Arendal

UNEP (2012). Avoiding future famines: Strengthening the ecological foundation of food security through sustainable food systems. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya

World Bank (2012). Data accessed on Aug 30, 2012 at http://data.worldbank.org/

WRI. (2005). Navigating the numbers: Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy. World Resources Institute. Accessed online on Oct 22, 2012 at http://pdf.wri.org/navigating_numbers.pdf

by Stefan Schwarzer